– Article by Linda Powers Tomasso, Project Associate, Center for Health and the Global Environment, Harvard University School of Public Health

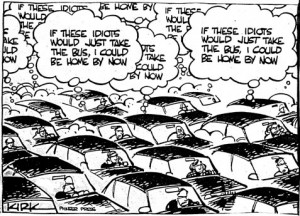

Climate change is in the news almost daily, and while many of us didn’t grow up with the phrase, our attentiveness to the causes of a warming planet gives us no cause for comfort. Our own decisions to adopt a more sustainable lifestyle sometimes seem futile—a drop in the bucket in the face of power plant emissions, or transport emissions emanating from 1,000 tailpipes backed up on I-91. How can we not feel like helpless bystanders vis-a-vis the enormity of response which climate change requires?

One of the perceptual challenges that prevents individuals from owning the problem of climate change is the economic concept of public vs private goods, an idea now being applied to environmental policy. In his seminal 1968 article, Garrett Hardin explained The Tragedy of the Commons as a situation when individuals act in their own best interest at the expense of the common, or public, good. Whereas the colonialists squabbled when the neighbor’s sheep overgrazed the town green, endangering the collective benefit of a public good, the public good of our time is climatic stability. Maintaining our climate within an acceptable band of temperature rise will not just influence other public environmental goods, such as species preservation, tolerable air temperature, fresh waterways free of salt-water intrusion. It will even impact some private goods, such as the safety of our beach house at the Connecticut shore due to storm surges, or the price of our breakfast cereal due to crop failure.

Recognized perceptual challenges limit our willingness to accept the evidence of climate change and impede policy momentum toward its solution. One of these challenges is the invisibility of harmful CO2 (think of the dangers of carbon monoxide, an odorless, tasteless, non-visible but still highly noxious gas). A similar situation exists with atmospheric carbon: we can measure glacial melt, capture icebergs cascading into the Antarctic Ocean on film, and chart temperature rise across decades. But an accruing CO2 concentration remains as hidden to the naked eye as your average flu virus, making it easy to relegate corrective action to another place, another time, another climate summit.

Postponement of large public investment to mitigate the causes of climate change is easy to justify for another reason. A time lag of about one hundred years exists between curtailed fossil-fuel use and measured reductions in CO2 concentrations, owing to its chemical persistence in the atmosphere. Show me an elected official who wants to spend his or her political capital (and budget resources elsewhere in demand) on benefits the electorate not only cannot visualize but will not even live to see? Why not put off today what you can do tomorrow….after all, we’re only human, and thus the linguistic root behind “anthro”-pogenic emissions, the cause of today’s abnormal CO2 level of 400 ppm.