It is generally accepted by climate scientists that New England will experience a trend of increasing intensity and frequency of storms resulting in an increase in flooding and coastal erosion. Recent storms have raised our collective awareness of the damage, both fiscal and physical, that these storms can cause. Consider that Sandy wasn’t even a hurricane when it hit Connecticut; it was a mere tropical storm. Yet federal funding for Sandy relief in Connecticut amounted to over $360 million. If you include New York and New Jersey, Congress approved over $60 billion in emergency disaster aid for Hurricane/Tropical Storm Sandy. That amounts to approximately $382 for every taxpayer (157 million taxpayers) in the country. If these types of storms become more frequent, it raises the question: Just how are we going to pay for it?

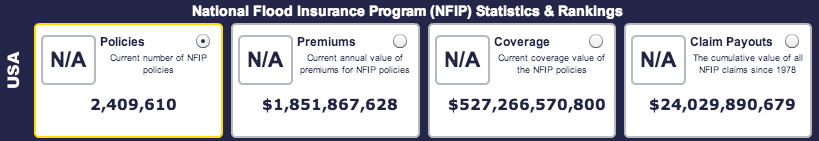

Well there’s the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). That’s the program, passed by Congress in 1968 and currently administered by the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA), where people with structures in flood-prone areas can buy flood insurance that is underwritten by the federal government. The NFIP was originally created to provide coverage to homeowners who could not find flood insurance on the private market. For pre-existing homes and businesses, owners were able to obtain insurance at low rates that did not reflect the property’s real risk.

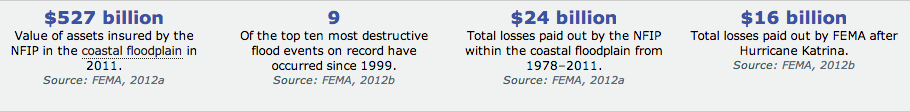

With the 100-year storm now possibly occurring every 50 years, or more frequently, the costs and consequences of flooding are dramatically increasing. And the NFIP has become the country’s second largest fiscal liability of the U.S. government, behind social security. The following information taken from NOAA’s State of the Coast website presents a sobering picture:

There are $527 billion of insured assets in the coastal floodplain alone for which taxpayers are currently responsible and that is only a portion of the overall NFIP liability. The program is seriously underfunded.

To address this issue, Congress passed the Flood Insurance Reform Act of 2012. According to the FEMA website (http://www.fema.gov/national-flood-insurance-program): “Key provisions of the legislation will require the NFIP to raise rates to reflect true flood risk, make the program more financially stable, and change how Flood Insurance Rate Map (FIRM) updates impact policyholders.” According to Director Craig Fugate of FEMA, rates for those who buy flood insurance through the federal government are expected to rise dramatically in the coming years. Homeowners who buy insurance through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) can expect premiums that currently cost several hundred dollars to increase to several thousand dollars over the next three to five years. Homeowners who live in areas of high risk and have not elevated their homes will feel the pain the most. The rate increases are scheduled to be phased in, with rates on secondary homes going up this year. Rates on primary homes will increase next year.

So how does all this affect the debate about our response to the impacts of climate change? As a nation we are sometimes slow to embrace change when it results in a change in our lifestyle. This is especially true when the change is perceived to be a “sacrifice,” and the end results will not be felt for decades or longer. With the help of NFIP, people have been able to rebuild homes in high risk areas with little or no financial risk to themselves.

We collectively have been slow to take a proactive stance when addressing the impacts of climate change. We don’t want to think about the future and make changes today that will benefit our children and grandchildren, if it involves sacrifice on our part. After all, it’s too costly — and we really don’t know that climate change is happening, do we?

Recent storm events and the associated costs have started to change people’s attitudes toward climate change and the need to do something. When serious money enters the picture, we seem to take greater notice. And, if predictions are accurate, we have only started to feel the fiscal impacts of climate change, some of which we are only beginning to understand. What is going to happen to the value of waterfront homes when the cost of flood insurance truly reflects risk? Or, if the decision is made that you will be covered for losses once and after that you are on your own. What does that do to a community’s tax base? Consider that sea levels are predicted to rise by 6.5 feet by the end of this century, causing billions of dollars of property damage in the low lying areas of cities like New York and Boston. If you factor in storm surge above and beyond sea level rise, the losses become staggering. What’s the solution? Do we move people out of high risk areas? Look to structural solutions like sea walls? How much will each of those options cost?

To date we may not have moved as quickly as we should have to develop a serious response to climate change. When money starts to frame the debate, that will change.